Born to Run (Away from Heteronormativity)

Our Working-Class Hero is Also a Soft-Butch Icon

This post is written by Jami Smith of the publication and community radio show Songs That Saved Your Life. Enjoy!

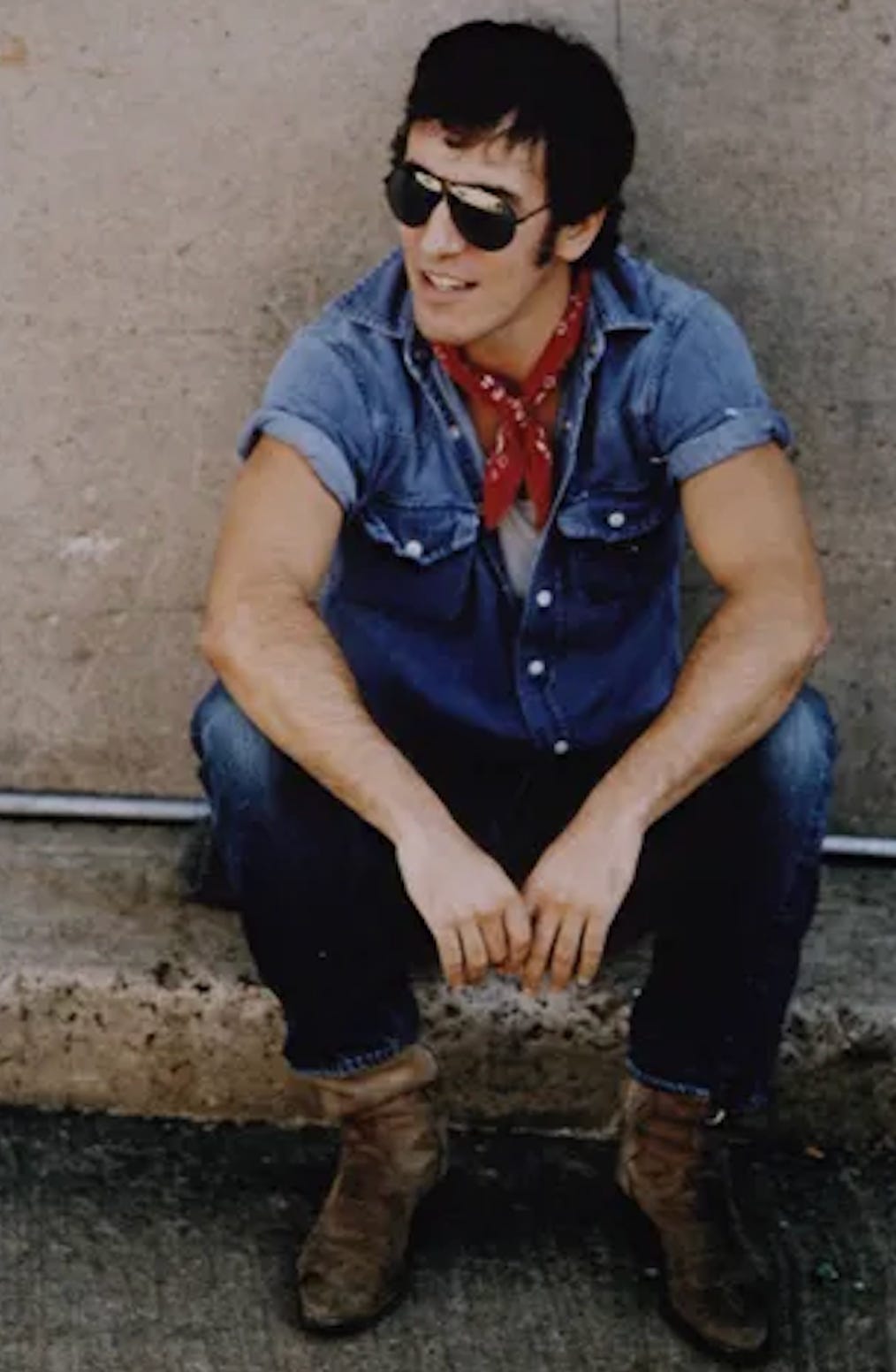

The thin white T-shirt that clings perfectly to glistening biceps barely contained by rolled-up sleeves. Or sometimes there aren’t sleeves at all. They’ve been cut off to reveal more muscle. This sweat and denim, paired with an old guitar and dreams of making it out of this town alive, are what we think of when conjuring the image of Bruce Springsteen.

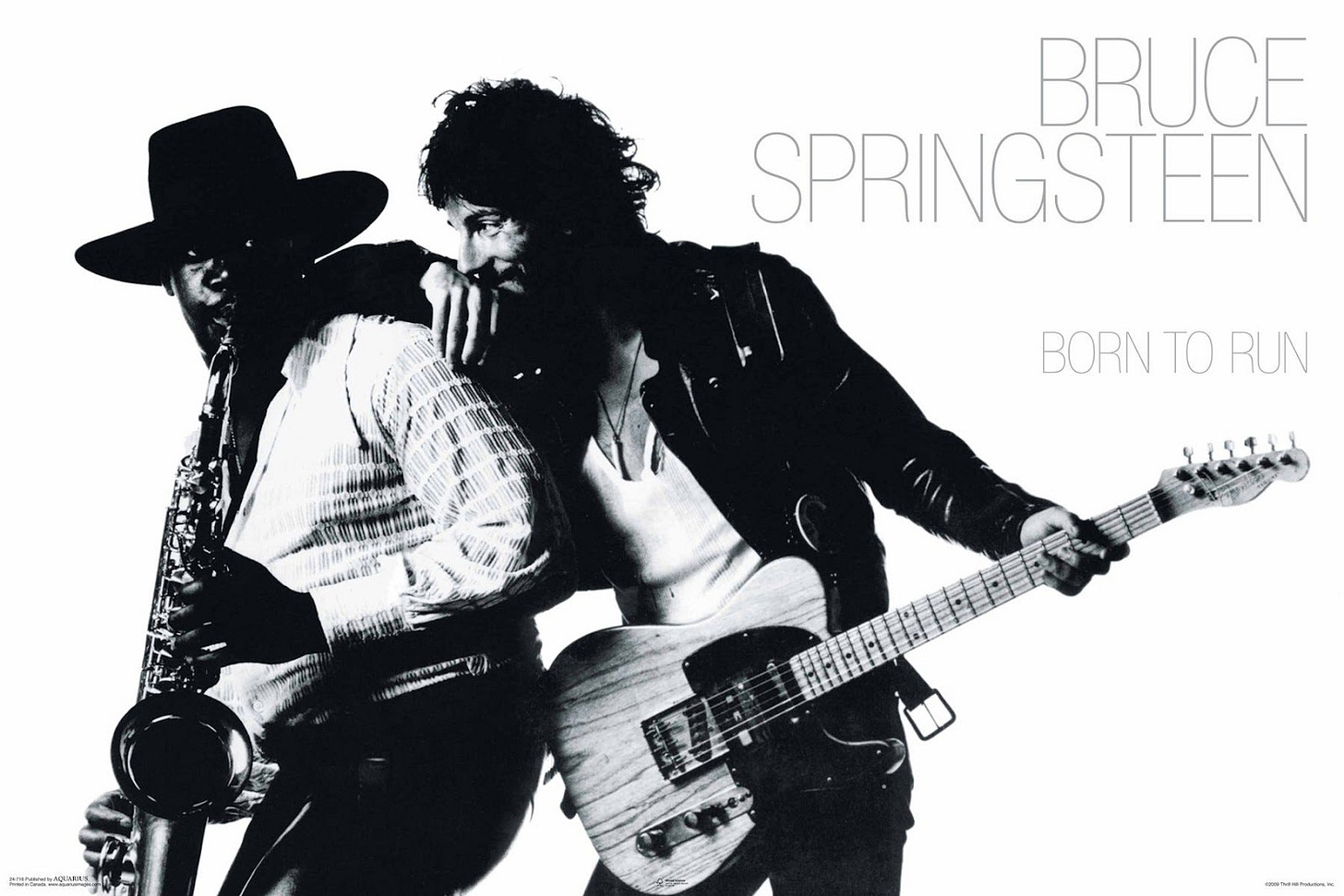

The Boss’s 1975 breakthrough album, Born to Run, is mythologized as the embodiment of straight, white, working-class masculinity. Except something’s off about that picture.

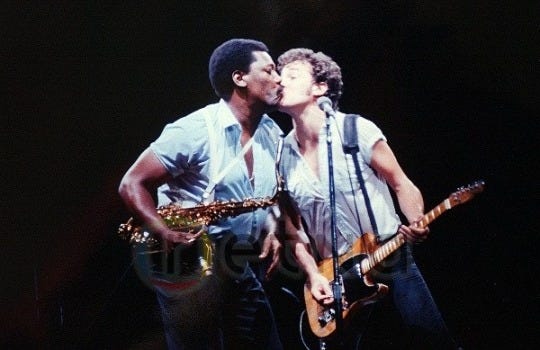

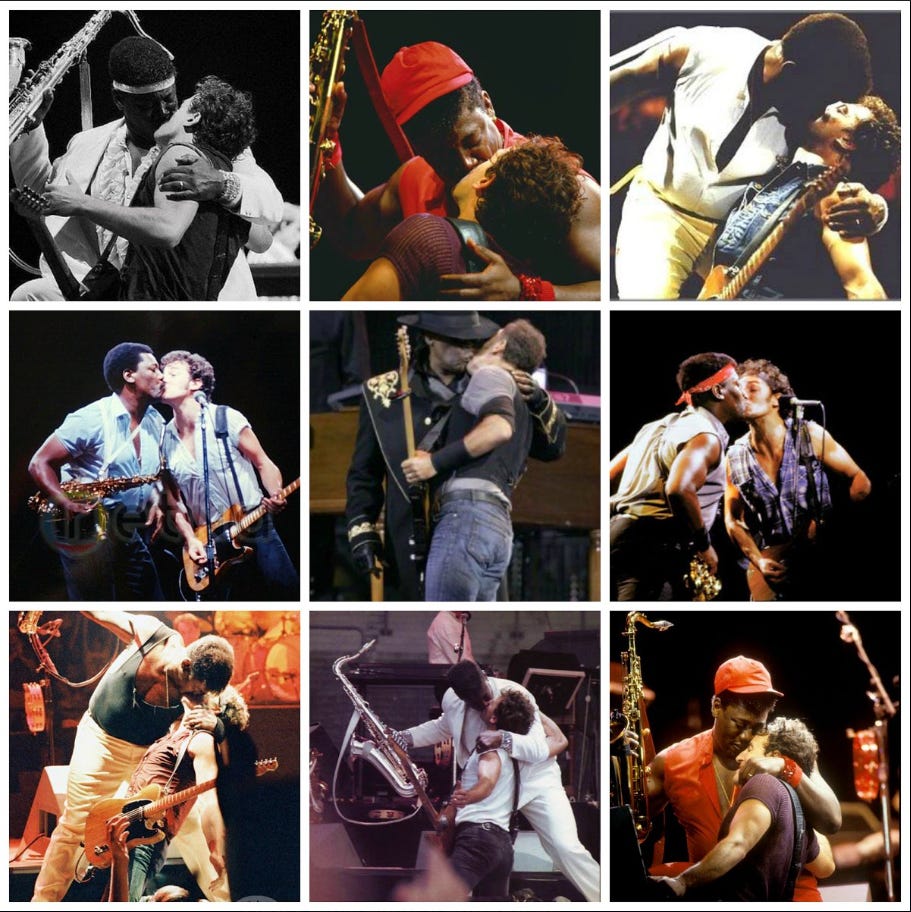

Is it because Springsteen’s music often depicts queer life? Or maybe it’s his fraught relationship with his father, who thought of him as “too sensitive.” Or it could be all of the times we’ve seen him full on MOUTH KISS his E Street Band mate Clarence Clemons.

More likely, it’s all of the above that complicates Springsteen as an icon of heteronormativity. The truth is always way more interesting. And it offers up a healthier version of masculinity that isn’t afraid of queerness, softness, or vulnerability.

The quintessential Springsteen song centers outsiders and dreamers surviving on the edge of American promise. For queer listeners, that estrangement feels familiar. Consider 1984’s “Dancing in the Dark.” While remembered as a pop hit, its lyrics carry a language of transformation and isolation: “I wanna change my clothes, my hair, my face.”

The song’s restlessness echoes the queer desire to shed any socially imposed identity in search of authenticity. Given its release in an era when queer visibility was scarce, the song’s yearning for connection and recognition reads as queer longing.

Holly Casio, host of the podcast Because The Boss Belongs To Us, explained, “The lyrics of that song just made me realize, oh my God, this is about me and my life. … [T]here’s a particular line where he says, ‘there’s something happening somewhere, baby, I just know that there is,’ and this feeling I had of, like, complete isolation when you’re a queer teenager in a small town, when the Internet doesn’t really exist yet, and you don’t really have connection to queer people and queer communities, that was such a tangible line for me. It didn’t feel like just a throwaway pop song anymore. It felt like this is a queer anthem.”

Springsteen’s embrace of queer emotion wasn’t only subtle. It could be in your face, as was the case with “Streets of Philadelphia,” written for Jonathan Demme’s 1993 film Philadelphia. Amid the AIDS epidemic, when public discourse routinely dehumanized those affected, the song compassionately portrayed queer suffering. The video, featuring Springsteen wandering the city intercut with scenes of Tom Hanks as a gay man dying of AIDS, pushed queer grief squarely into the mainstream.

While “Streets of Philadelphia” might be the most obvious example, several songs invite queer interpretation. Take 1975’s “Backstreets,” about our protagonist’s love for someone named Terry. The gender-neutral name could be short for either Terrence or Teresa, though the spelling is more often associated with the masculine. The name’s gender ambiguity leaves the door open, but the longing inside is unmistakable.

Remember all the movies, Terry, we’d go see

Trying to learn to walk like the heroes we thought we had to be

And after all this time, to find we’re just like all the rest

Stranded in the park and forced to confess

To hiding on the backstreets

We imagine two teenage boys watching “real” men onscreen, trying to act the part. These two characters hang out in the shadows of town where they can get drunk, do drugs, and apparently slow dance.

Slow dancing in the dark on the beach at Stockton’s Wing

Where desperate lovers park, we sat with the last of the Duke Street Kings

Huddled in our cars, waiting for the bells that ring

In the deep heart of the night they set us loose of everything

To go running on the backstreets

Running on the backstreets

Terry, you swore we’d live forever

Taking it on them backstreets together

Endless juke joints and Valentino drag

Where famous dancers scraped the tears up off the street, dressed down in rags

Similarly, 1984’s “Bobby Jean” sounds like a narrative of queer solidarity. It can be interpreted as a first love between teenage outcasts who found safety and protection as a couple.

Me and you, we’ve known each other

Ever since we were 16

I wished I would have known

I wished I could have called you

Just to say goodbye Bobby Jean

Now you hung with me when all the others

Turned away turned up their nose

We liked the same music, we liked the same bands

We liked the same clothes

The line “we liked the same clothes” certainly strikes a chord with lesbians who didn’t fit the confines of feminine standards. And Springsteen doesn’t try to win back Bobby Jean, doesn’t pine for her return. Instead, he wishes her luck as she heads toward freedom, searching for something bigger than their small town could ever give.

Yeah, we told each other

That we were the wildest

The wildest things we’d ever seen

Now I wished you would have told me

I wished I could have talked to you

Just to say goodbye Bobby Jean

Now we went walking in the rain

Talking about the pain from the world we hid

Now there ain’t nobody, nowhere, no how

Gonna ever understand me the way you did

In 1988, Springsteen also featured queer couples in the music video for “Tougher Than the Rest.” The video cuts between Springsteen singing a romantic duet with future wife Patti Scialfa and shots of couples kissing, cuddling, laughing. Queer couples, too. No spectacle, no explanation, just ordinary intimacy. To show that in 1988, in a Boss video no less, was quietly revolutionary.

It isn’t just the music that draws queer listeners to Springsteen. There’s something about the way he performs gender. There’s a paradox to his masculinity. Springsteen’s stage persona exemplifies what author Jack Halberstam might describe as a form of female masculinity in reverse: a cisgender man embodying hyperbolic butchness so stylized it verges on camp.

Springsteen wore the costume of American butch — the jeans, leather jackets, and muscle tees — but he sang with the heart of an outsider. If you tried to assemble a Halloween costume of The Boss, you’d end up looking like any given lesbian shooting pool at Ginger’s on a Tuesday night.

His relationship with his father was famously fraught. Springsteen was too sensitive, too artistic, too gentle. His dad couldn’t see himself in his son. For many queer kids, that story hits close to home.

Springsteen told The Advocate (!) in 1996: “I think when I was growing up, that was difficult for my dad — to accept that I wasn’t like him, I was different. Or maybe I was like him, and he didn’t like that part of himself — more likely. I was gentle, and generally that was the kind of kid I was. I was a sensitive kid. I think most of the people who move into the arts are. But basically, for me, that lack of acceptance was devastating, really devastating.”

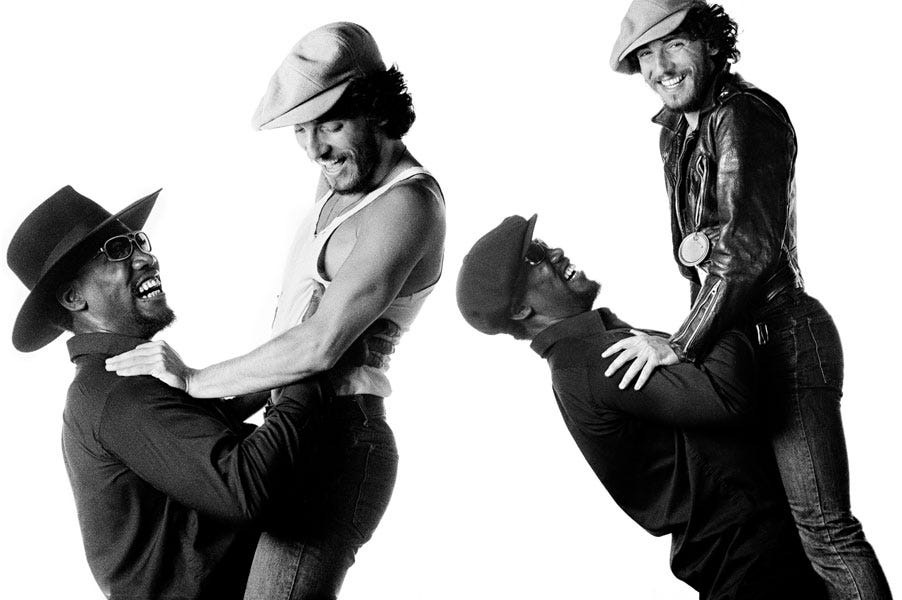

Springsteen’s outward image of American manhood gets further subverted when you consider his male relationships, especially his love for E Street saxophonist Clarence Clemons. Their friendship is so intimate that they would often kiss onstage in front of an arena full of the kind of people who might otherwise be shocked.

Acts of intimacy might seem sensational when we aren’t accustomed to examples of healthy masculinity where men can be emotionally open, physically affectionate, and unafraid of intimacy.

Clemons was asked to describe their relationship in an Associated Press interview, saying, “There’s no sexual connotations at all. It’s just friendship and joy…two androgynous beings becoming one person for a second. It’s love. It’s more than being married or male and female. Two very virile men finding that space in life where they can let go enough of their masculinity to feel the passion of love and respect.”

Bruce Springsteen may not be queer, but he’s certainly one of ours.

His queerness, in other words, is less about identity than resonance. His music gives voice to living at the edge of acceptance, the desire for escape, and the costs of love under constraint. His butchness isn’t a barrier but an entry point, an exaggerated performance of masculinity that, paradoxically, reveals its own fragility.

“Certainly tolerance and acceptance were at the forefront of my music,” Springsteen told The Advocate. “If my work was about anything, it was about the search for identity, for personal recognition, for acceptance, for communion, and for a big country. I’ve always felt that’s why people come to my shows, because they feel that big country in their hearts.”

For these reasons, many embraced Springsteen as an “honorary lesbian,” a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of how thoroughly his music captures queer sensibilities. His songs remind us that queerness isn’t only about who we love, but also about how we experience the world if we insist on authenticity against the odds.

Thanks for reading Lavender Sound. We urge you to take a second to read about the fact that Israel continues to bomb Gaza after the ceasefire, and that the United Nations has said the state of Israel is committing genocide yet has greenlit a “peacekeeping” plan that further disenfranchises the Palestinian people.